« July 2014 | Main | August 2016 »

May 20, 2016

Diving South Florida May 2016

Sunday, May 8, 2016 — It's been almost two years since we went diving. The culprit was a combination of taking a breather after all those many dive trips that led to the publication of my book (Becoming a Scuba Diver), an increase in workload, and then preparation and execution of our move from California to Tennessee. We had postponed diving again and again. But that was about to change.

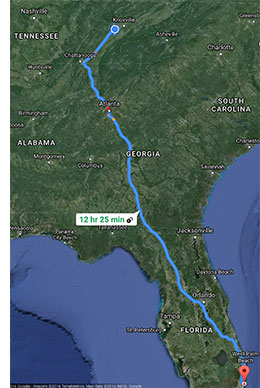

Our friends Tom and Donna own a timeshare in Pompano Beach, Florida and invited us to come along for a week. Pompano Beach, just north of Fort Lauderdale, is within driving distance of our home in East Tennessee, and so we gladly accepted. We were to drive down, convoy style. Our friends in their mighty Diesel-powered Ford F350, we in the Prius.

Our friends Tom and Donna own a timeshare in Pompano Beach, Florida and invited us to come along for a week. Pompano Beach, just north of Fort Lauderdale, is within driving distance of our home in East Tennessee, and so we gladly accepted. We were to drive down, convoy style. Our friends in their mighty Diesel-powered Ford F350, we in the Prius.

Prior to departure we spent days going through our dive gear, some of which we first had to find in various parts of our new home where still not everything is where it should be after the move. We found things that didn't work. The battery in my Uwatec Galileo Sol dive computer needed to be replaced, and the battery of the wireless transmitter screwed onto my regulator was dead, too. The transmitter takes one of those button batteries, not the popular CR2032, but the less common CR2450. Fortunately, the local Walgreen's had one of those, and replacing it was easy.

I always suffer from logistics anxiety before a dive trip. Do I have everything? How do we get to the boat? What will the dive operation do and what do I need to do? What do I need to bring? Where can I stow my gear? Can I leave things at the dive shop, or do I have to take it back to where we stay? What temperatures can we expect, and which wet suit should I bring? And so on. These questions are always on my mind before a trip.

We got up at 3AM on Saturday, left at 4:30, and the 820 mile trip from East Tennessee to South Florida, though long, was pleasant. I had forgotten just how green and hilly northern Georgia is, and how much I enjoy long rides in a car where one can talk, relax, stop wherever one wants, and always has enough legroom.

I hate toll roads and mercifully Tennessee and Georgia don't have any. Florida does, though, but there's SunPass, an RFID-based electronic payment system. Interestingly, one can get the RFID sticker in a vending machine next to candy bars and salted snacks, and then easily activate it on a smartphone or tablet.

Once in Florida and all checked in and settled in our home for the week, the dive shop, Pompano Dive Center, turned out to be right next to a marina with their dive boats. I got answers to all my logistics worries, as I almost always do.

The marina was at an intracoastal waterway parallel to the beach. That meant motoring past gorgeous waterfront homes for a mile or so, under bridges and past boat yards before the captain could take the boat, the Sea Siren, out onto the open water.

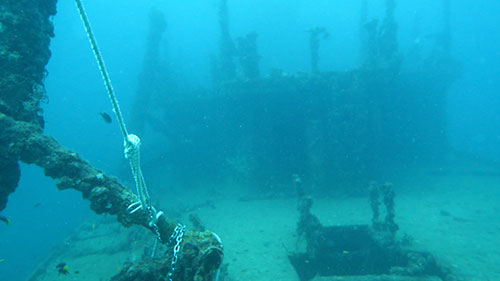

The first dive of the week was to the wreck of the Captain Dan, a 175-foot tender that was sunk as an artificial reef a quarter of a century ago. Opposite me sat five divers with rebreathers, which seemed incredibly complex to me.  The idea of a rebreather is so simple: instead of wasting all this air by just breathing it out into the water as one does with open circuit scuba, rebreather divers are on closed circuit, where exhaled air is scrubbed of carbon dioxide, the inert nitrogen reused, and only as much oxygen added as is needed. But that's a complex mechanism, with sensors and systems and checks and balances.

The idea of a rebreather is so simple: instead of wasting all this air by just breathing it out into the water as one does with open circuit scuba, rebreather divers are on closed circuit, where exhaled air is scrubbed of carbon dioxide, the inert nitrogen reused, and only as much oxygen added as is needed. But that's a complex mechanism, with sensors and systems and checks and balances.

We had brought our own tanks, but I had never actually dived with the particular combination of suit and tank (5-mil wetsuit, 100 cubic foot steel tank) and so didn't know exactly how much weight I needed in the pockets of my BC. I probably didn't need any but decided on 8 pounds. We arrived at the wreck site, the boat tied off, and it was time to jump in. At 80 degrees, the water was warm enough to feel nice and pleasant.

After having stored my dive gear for two years and then moved it across the continent in a hot POD container before having it sit in a hot garage for another few months, I first had to shake an uneasiness about everything still working as it should.  After all, scuba gear is life support equipment where failure is not an option.

After all, scuba gear is life support equipment where failure is not an option.

I've never liked anchor line descents, which is how it's usually done when you go visit a deep wreck. If you don't use a line and just float down you may actually miss the wreck, especially in current and poor visibility. But hanging on to a line that disappears in the distance is disconcerting to me.

This time I was glad that there was a line, because my completely dry wetsuit was too buoyant to let me descend easily even with eight pounds of weight in my pockets. Once down to 20 feet or so descending became easier.

There was no current and the visibility was reasonable. The wreck came into view, sitting on a sandy bottom. It was encrusted with all sorts of marine growth, and though it was pretty deep, the feel of this dive was considerably less intimidating than diving the wreck of the Yukon in San Diego at roughly the same depth. That's because the Yukon is usually in near dark, and the Pacific water is cold. The gloom of the Yukon prohibits even the thought of entering the wreck, whereas the warmer water and greater light almost invited exploring the insides of the Captain Dan.

The wreck sat in sand at a depth of 110 feet. We touched bottom, then swam around the ship, and I quickly became more comfortable with my gear and being underwater again. Exploring was cut short, though, because even with 32% Nitrox in our tanks, bottom time at that depth is limited. Even with a slow ascent and the mandatory deco stop at 15 feet, it was a fairly brief 40 minute dive.

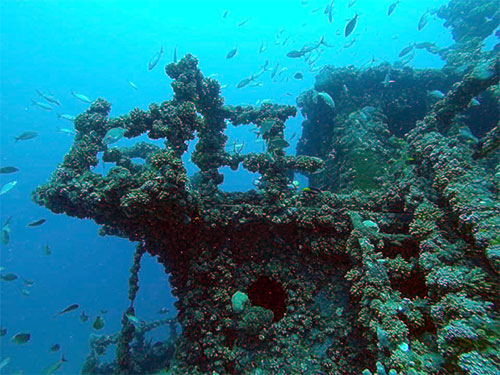

The second dive was at a similar nearby wreck, the 160 foot tender RSB-1. Normally diving starts with the deepest dive of the day and then proceeds to shallower ones, but the RSB-1 sat at 120 feet, so we had two fairly challenging dives right off the bat. Visibility at the bottom was quite good on this dive, probably 60 feet or even more, which meant we were in for a treat.

The second dive was at a similar nearby wreck, the 160 foot tender RSB-1. Normally diving starts with the deepest dive of the day and then proceeds to shallower ones, but the RSB-1 sat at 120 feet, so we had two fairly challenging dives right off the bat. Visibility at the bottom was quite good on this dive, probably 60 feet or even more, which meant we were in for a treat.

Seeing a coral-encrusted wreck that has been down for decades in good light and clear water is quite an experience. The difference between seeing a lot of a wreck and groping around in the near dark is vast. Unfortunately, even with Nitrox, exploring at 100+ feet meant that remaining bottom time quickly reached the single digits on our dive computers. and so this dive was over far too soon as well.

Speaking of dive computers, I nearly lost mine on this dive. At a depth over over 100 feet its wristband broke apart and it was only by coincidence that I happened to look at it just as it let go. It would not have tumbled into unrecoverable depth as I was hovering close to the sandy bottom when it happened, but I probably still would not have found it had it fallen off unnoticed. I always wear a backup computer, and so I could have safely completed the dive with the backup, but losing an expensive dive computer definitely is no fun. And the wristbands of expensive dive computers should not simply break.

Back on the boat it felt great to have reacquainted ourselves with diving again. And having ready access to a good dive shop came in handy, too, for the broken wristband of the computer. They didn't have a replacement in stock, but took one from a new computer and put it on mine.

Monday, May 9, 2016: Current — Normally dive boats go out on two tank routes, but sometimes it's three. And that's what we were going to have on our second day of diving off Pomano Beach, a three tank dive with an onboard barbecue.  That meant having a grill and a lot of tanks on the boat, but there were only eight divers and so we could spread out.

That meant having a grill and a lot of tanks on the boat, but there were only eight divers and so we could spread out.

The sea was rougher than the day before and it was windy, so we were in for a bumpy ride, and a long one, too. All in all, between intracoastal and open water travel, it took a good hour until the Sea Siren slowed down for its first destination of the day. The MV Castor is a 258-feet ship that was sunk in 2001 after she had been seized by the US Coast Guard for transporting illegal drugs. Apparently, a good number of the scuttled ships off the coast of South Florida are former drug runners.

Once a dive boat arrives at a wreck location, which thanks to GPS coordinates and depth sounders is far easier than it used to be, the first thing is to tie off the line that goes from a permanent buoy to the wreck. If there is a permanent buoy, which isn't always the case. Then dive masters first must go down to the wreck to attach a line. The other reason for dive masters to go in first is to report on the conditions. Everyone hopes to hear that the visibility is good and there is no current.

Once a dive boat arrives at a wreck location, which thanks to GPS coordinates and depth sounders is far easier than it used to be, the first thing is to tie off the line that goes from a permanent buoy to the wreck. If there is a permanent buoy, which isn't always the case. Then dive masters first must go down to the wreck to attach a line. The other reason for dive masters to go in first is to report on the conditions. Everyone hopes to hear that the visibility is good and there is no current.

Alas, no such luck on that dive. The current was very strong, abating just a bit down by the wreck. That meant jumping in the water and instantly grabbing the line, or else one might get washed away. We did that, Carol and I, and began the ascent down the anchor line. The current was so strong that we had to hold on with both hands, pulling ourselves down hand over hand. Between the current, holding on to cameras, and clearing ears (which can be more difficult in strong current) it was slow going.

After what seemed like an eternity, the big wreck came into view and visibility turned quick good. The current lessened a bit, but not enough to make letting go of the line seem like a good idea. I chanced it anyway, dropping down to the sandy bottom at 115 feet in the hope of finding calmer waters there. That didn't happen and what one then does in such situations is hunting for spots with less current in and around the wreck. I found some places but still had to fight current, which makes diving that much harder.

It would have been great to explore this whole very interesting wreck, the midsection of which had mostly collapsed. There was lots of life and much to explore. A big attraction here were the goliath groupers that had taken up residence in and around the wreck. They hung around, fearlessly eyeing us divers and being quite inquisitive. One seemed particularly interested in my bright orange ScubaPro Seawing Nova fins.

And then there are the colors that no one expects and which only reveal themselves in the beam of a dive light or a flash.

Since this again was a deep wreck, we had very limited bottom time before heading back to the anchor line for our way up. Finding the anchor line again is always a bit of a harrowing experience for me. Without the line ascent is difficult and disorienting in waters, and one might surface well away from the boat. I did locate the line and the current up was even stronger than on the way down. I was exhausted by the time I surfaced.

The buoy was now in front of the bucking Sea Siren and not in the back where the ladder is. I couldn't see a line around the boat and didn't want to let go of the buoy, but knew I couldn't stay where I was. The catch line, of course, was behind the boat with the current and I should have known that. By the time I climbed up the ladder I was panting and exhausted and felt quite sick.

I ended up passing on the second and third dive, feeling too queasy to get up. I even missed the barbecue. I don't know if I was seasick, but I felt miserable enough to wish I were in our room in bed without all the rocking. It was an unpleasant two or three hours until the feeling finally passed. During that time I felt like I never wanted to dive again. I also wondered what had happened to me, as everyone else seemed unaffected.

Tuesday, May 10, 2016: Rough Waters — We expected our week in Pompano Beach to be nice, easy diving, the sort of a tune-up we needed to reacquaint ourselves with diving. So far that hadn't been the case. Anchor line dives to deepwater wrecks, long rocky boat rides and strong current didn't qualify as easy. And so on the morning of our third day my stomach still felt a bit queasy. But there was another gorgeous sunrise and on the agenda was the Tracey a comparatively shallow (70 feet) wreck not too far away from our location.

But Neptune didn't cooperate. As soon as we exited the intracoastal waterway and hit the open ocean the water was rough. The boat bounced and plowed through increasingly tall swells, with spray flying all over and things coming loose all over the boat. The usual 2-foot waves became four, five and probably even six footers, with whitecaps all over. Our fairly substantial 46-foot dive boat rocked enough to make getting off for diving seem hazardous, and getting back on the boat even more so.

But Neptune didn't cooperate. As soon as we exited the intracoastal waterway and hit the open ocean the water was rough. The boat bounced and plowed through increasingly tall swells, with spray flying all over and things coming loose all over the boat. The usual 2-foot waves became four, five and probably even six footers, with whitecaps all over. Our fairly substantial 46-foot dive boat rocked enough to make getting off for diving seem hazardous, and getting back on the boat even more so.

The conditions hadn't improved when we arrived at our destination, and Carol and I decided to skip the dive. In dive certification class, instructors are fond pointing out that there are old divers and there are bold divers, but there aren't any old, bold divers. The risk of getting hurt in such rough conditions seemed more than we were willing to accept. With the back and front of the boat rising and then dropping six feet or more, the chance of getting hit by the boat or the loose ladder felt simply too large.

The rest of the guests on board did do the dive, I felt a bit like a wuss, and we breathed a sigh of relief when everyone was safely back on board.

Conditions didn't improve and we didn't do the second dive either. This was a drift dive with each group of divers taking along a dive flag and reel. Thirty minutes or so after the first divers had jumped in, people began popping up here and there in the ocean, with the crew looking out for them and motoring over to pick them up. I thought each diver should probably deploy a safety sausage.

I did feel quite bad over skipping two more dives, making it four in a row, more than I had ever missed before in one stretch. But it simply seemed the right thing to do.

Later in the day we drove down to Hollywood where we visited the largest dive shop I had ever seen in my life. Then it was dinner and drinks at Margaritaville. The drinks were good, but the whole Margaritaville experience didn't quite live up to expectations.

Wednesday, May 11, 2016: Back in the drink! — If you get thrown off a horse, they say, get right back up in the saddle. That sounded like good advice after having missed those dives. I did not want to get in the habit of bowing out of dives for minor reasons.

So I hoped that all would go well the next time out. And it did. The water looked much calmer from the balcony of our place, and once in the boat and on open water, the waves were indeed much smaller. The day's dives started with the 170-foot Sea Emperor, which despite its impressive name is really a hopper barge. She was sunk with 1,600 tons of concrete drainage culverts on board, a good part of which ended up laying next to the barge because she flipped over as she went down.

There wasn't much current going down and the visibility was quite good. The spilled culverts made for a great habitat for all sorts of life and exploring it was interesting. And the wreck's depth at 75 feet meant a longer dive.

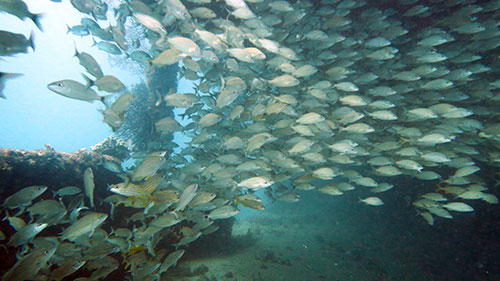

Despite the barge being upside down, it was easy to get inside and dive in and between the compartments, many of them teeming with fish. Every chamber had access to the open water, so there was plenty of light and no chance to get lost.

While current is a challenge when visiting wrecks it's also what makes drift dives possible. There the idea is to have the current take you along for a ride. It's a great way to relax and just watch the scenery go by. We had been told that the South Florida reefs were modest and nothing worth writing home about, but that turned out to be quite wrong.

The reef area at about 60 feet that we drifted over for an hour was interesting and quite impressive. We saw hundreds of barrel sponges and all sorts of life in an endless variety of slopes and ridges with the occasional overhang. There weren't walls or the kind of massive coral heads like you see, for example, in Roatan, but it was better and larger than the reefs in many other dive areas with a much greater reputation for good reef diving than Pompano Beach.

The barrel sponges weren't quite as large as we've seen elsewhere, but what they lacked in size they made up in numbers. Spiny lobsters found holes to live in and defend, as did a good number of moray eels. We didn't see too many lion fish, which is a good thing for the native critter population. A green turtle didn't mind our visit and let us get close for some pictures and video.

Even after a good many dives in my life, I am still amazed how conditions affect everything. Rough sea can be nauseating and even keep you from diving. The sun adds light underwater and makes you feel warmer, whereas an overcast day can make dives feel cold and gloomy. Current can be a total pain as getting down to and back up from an anchor line dive becomes all about getting there and back again instead of enjoying the actual dive. Waves can make getting back on the boat stressful and even dangerous. Being able to spread out on a boat is so much more comfortable than a sold-out trip. Then there are the ears and sinuses that may or may not cooperate no matter how much experience you have equalizing the pressure in your ears. And masks that may or may not fog up. Being cold can ruin even a great dive because it becomes all about the cold and somehow staying as warm as possible.

A few words about the importance of the right tanks. One of the benefits of driving is that we could bring along our own tanks, two steel 100s for me and two steel 80s for Carol. That's different from the ubiquitous aluminum 80 tanks used by almost all resorts, liveaboards, and dive operations. Steel is less buoyant than aluminum and therefore requires carrying less weight. I also liked having the 100 cubic foot steel tank because, despite being the same external size as an aluminum 80, the extra 25% of air means one is hardly ever low on standard dives.

Thursday, May 12, 2016: Wrecks aplenty — While San Diego's "Wreck Alley" is famous for its ship wreck diving, in terms of the sheer numbers it is dwarfed by what's available off Pompano Beach and neighboring communities in Florida.  There are literally dozens of wrecks laying off the coast here. They range in length between under 100 feet all the way to over 400 (the Lowrance), and sit in waters as shallow as a few dozen feet all the way to 250+ feet for technical diving. Most, but not all, were sunk as artificial reefs, and at that they succeeded admirably.

There are literally dozens of wrecks laying off the coast here. They range in length between under 100 feet all the way to over 400 (the Lowrance), and sit in waters as shallow as a few dozen feet all the way to 250+ feet for technical diving. Most, but not all, were sunk as artificial reefs, and at that they succeeded admirably.

And while the waters off San Diego are perennially cold, the South Florida seas are warm and pleasant. We saw 78-82 degrees in early May. Current can be an issue, as can be visibility, but overall, if there's a wreck alley, South Florida certainly has a strong claim.

While few divers will list Pompano Beach as one of their preferred diving locations, that's just because the diving here is comparatively little known. We had expected some easy, shallow diving to brush up skills. Instead, our first two dives were to 110+ foot wrecks, one right after the other. The next day another big, deep wreck with current so strong that it ranked among the top ten most challenging dives in my 350 grand total. So this is serious, interesting diving here.

But to get back to our adventures, this day started off with a dive down to the wreck of the 215-foot Dutch freighter Rodeo-25, sunk in 1990 and sitting in 130 feet of water on a sandy bottom. There was no current going down or back up, and 100-foot visibility made for an awesome dive. It's always great to see large parts of a wreck and not just what's right before your nose. Light and visibility help to convey a sense of the true size of a wreck.

But to get back to our adventures, this day started off with a dive down to the wreck of the 215-foot Dutch freighter Rodeo-25, sunk in 1990 and sitting in 130 feet of water on a sandy bottom. There was no current going down or back up, and 100-foot visibility made for an awesome dive. It's always great to see large parts of a wreck and not just what's right before your nose. Light and visibility help to convey a sense of the true size of a wreck.

Here, again, we ran smack into the limitation of allowable bottom time. The dive shop had thoughtfully filled our tanks with just 29% Nitrox instead of 32%, thus increasing maximum depth from 111 feet to 126 feet, just enough for me to touch the sand next to the wreck. Swimming around the wreck still meant to be at a depth of 100 feet, quickly munching up remaining bottom time. The rear part of the wreck with the bridge and masts was much taller and made for a shallower dive level, but since the anchor line was attached to the lower bow all divers had to return there. I stayed fairly high on my return from the masts to the bow and anchor line, and still got down to just one minute of no-decompression time on my computer. Most others had certainly gone into deco time.

Given the depth of this first dive, we made the second dive a nice, pleasant drift over the reef, with lobsters, lion fish, morays, a scorpion fish and tons of other colorful life.

The rest of the day was quite eventful. We had dinner with old acquaintances, a couple that we had met a few years ago on a liveaboard trip around Turks and Caicos. And our friends found, much to their dismay, that the battery of their truck was dead. That normally just requires a jump, but if the keys to the truck are inside the vehicle and its keypad lock has no power, it's a different matter altogether. Especially when it's a 7-liter diesel in a parking garage. The cause was obvious: an ice chest had remained connected and drained both batteries of the big vehicle. All attempts to get into the vehicle to at least pop the hood failed. But googling revealed a way to restore power and thus open the truck. And AllState roadside assistance arrived in the form of a dude with a Rastaman do in a Volkswagen. He got the job of jumping the big diesel done with two booster batteries helping the Volkswagen.

Friday, May 13, 2016: Four on the floor, and a hammer — Generally it takes a few days to become familiar with a dive operation. That's what happened to us on this South Florida adventure with the great folks at the Pompano Dive Center. Once we had become friends with all of them and knew how it all worked, who does what, and what goes where, it was already the last day of diving for the trip. But what a last day it turned out to be.

Our friends had left that morning to spend a day with family on their way back home, and we were the only divers on board. Just us, the captain, and two divemasters. So the crew outnumbered us. That can't be very profitable for a charter operation, and it showed again that apparently few divers know how great the diving in the Pompano Beach area is.

The water was all but flat, the sun was out, and we started the day with a return to the Captain Dan. Going back to a wreck for a more leisurely examination is always a treat. The conditions weren't the greatest but we got to do some of the penetrations we had skipped on the earlier dive. After a quarter of a century down there, the Dan is still almost completely intact, but covered with all sorts of small growth and it looks a bit muddy. If there's enough light or one uses a flash, though, colors pop up and the old wreck beautifully comes to life.

When the Pompano Beach dive boats don't go out with divers, they are engaged in a shark tagging project. Apparently that's a government funded attempt at learning more about the types, presence, and migration paths of sharks in the area. Personally I had a hard time imagining how the same dive boats we used also served as platforms to hook sharks, get them onboard, examine and tag them, and then let them go again.

After the deep Captain Dan, we decided on a leisurely drift dive to cap the morning. The current almost always runs south to north off the Florida coast, and since the wreck was south of the inlet the dive boat uses to get home to its port, the drift dive was on the way. They called this particular one "Razzle Dazzle," and it certainly lived up to its name. On that dive especially.

That's because just minutes into the dive along the 60 foot deep reef I looked to my left and found myself right next to a Hammerhead shark. That is definitely not a common occurrence, and certainly not on a drift dive near Pompano Beach, South Florida. Hammers usually swim in schools and they are shy, hardly ever getting close to divers. This one was alone and was no more than a few feet away from me.

The whole encounter lasted no more than a few seconds from when I first saw the sizable Hammer (it was larger than it looks in the picture below, due to perspective) and when it disappeared again behind me. Had I been surprised this way by a barking dog or a larger wild animal on land, I'd have experienced the familiar rush of adrenaline that instantly puts the human body on alert and in code orange condition. Yet, I felt none of that other than a "wow, this is so cool!" sensation.

Carol was right next to me and when I alerted her to the shark had the presence of mind to quickly raise her GoPro and takes pictures. Amazingly, she managed to capture a great shot. That served as proof that it had actually happened. She later said she was surprised about my calm reaction, as Hammerheads apparently can be pretty nasty.

In a way, however, it was no different from dives off West Caicos in the Caribbean where we'd been surrounded by reef sharks: a sense of wonder and excitement of seeing those magnificent creatures. Somehow fear never entered the mind. Maybe it's because unlike on land where you can instantly plan defensive or evasive action, in the water what you can do is so very limited that all a human diver can do is watch.

This was supposed to be our last dive of the trip, but Carol talked me into signing up for the afternoon dives as well. Only three had signed up for that and the boat needed a minimum of four to go, so it seemed the right thing to do, especially since we had missed those dives earlier in the week.

Of our fellow divers on that last trip out to sea were a father/daughter team with the girl being in her teens and on her very first dive after certification in a lake. Thinking back of my own first actual dive, going out on a dive boat for a 45 minute ride on the open ocean and then dive a 80-foot wreck down an anchor line seemed quite a challenge.

Of our fellow divers on that last trip out to sea were a father/daughter team with the girl being in her teens and on her very first dive after certification in a lake. Thinking back of my own first actual dive, going out on a dive boat for a 45 minute ride on the open ocean and then dive a 80-foot wreck down an anchor line seemed quite a challenge.

The wreck of the Tracey sat on sand at 70-80 feet in mediocre visibility, but it certainly was a treat. Under a large metal canopy were many thousands of fish. They love that kind of setting. There was also ample penetration and we explored some of that.

The sand around the Tracey was also favored by stingrays. We spotted one who let us get quite close before he took off, whirling up sand in the process.

Then I discovered markers away from the wreck and decided to follow those, as there were two other wrecks nearby. It was perhaps a 200 foot swim until another wreck suddenly loomed before us, likely the 95 foot long Jay Scutti, and so we got two wrecks in one. And an encounter with a giant grouper to boot.

There was not enough time to explore the wreck of the Jay Scutti as the third diver that had come along on my exploration was on a smaller tank and his air was getting low. So we returned to the Tracey and went up the line.

And, oh, before we departed for the second wreck, we saw the young lady diver happily swimming around the wreck! Good for her! She did just fine, too, on the drift dive that followed, having decent air consumption and apparently no fear. Her arms and legs were busy, as is almost always the case with new divers, but that'll change. She did not notice that a nurse shark made an appearance behind her. We told her later and she regretted not having seen it.

Saturday, May 14, 2016: Drive home: No lines, no hassles, no TSA — All dive trips begin and end with, well, the trip. This time that meant packing the car and then a long 830 mile drive each way. That took 13 hours from door to door. Which was actually more than most of the international dive trips we've done.

But I was reminded again how driving has so many advantages. While cramming gear and necessities into whatever the airlines allow is always a huge hassle,you simply put into the car whatever you think you may need. On this trip back home we had four big scuba tanks, two large scuba gear bags, clothing and toiletries, towels, food, camera bags, and assorted odds and ends. Far, far more than one could ever take on a plane.

And it's economical. The Prius needed just one fuel stop for the 830 miles to get from home to our destination. It used a grand total of 17 gallons of gasoline, which at an average of just over $2/gallon cost just $34 one way. Plus a great lunch at Joe's barbecue somewhere in the southern part of Georgia.

There is also no ridiculously expensive airport parking, no standing in long lines, no TSA hassles, no waiting for the plane, no boarding, no tiny rock-hard seats, no endless delays, no rush to the baggage claim, no long line at immigration, no hassles at customs, no hustlers, no surly gate agents, no cab or bus to the final destination. And when you're there, you have a car to go places, anytime, anywhere.

Right now I don't feel I ever want to set foot in an airplane again. Or have my luggage and my body searched one more time.

Posted by conradb212 at 1:28 PM