In this section we explain dive tables and go through specific examples of repetitive dives, using both the PADI and the NAUI tables.

Dive tables are used to determine how long you can safely stay under water

at a given depth, both for the initial dive and for subsequent dives.

To many aspiring scuba divers, Dive Tables are scary. It seems inconceivable that they'd ever understand them, let alone become proficient in using them.

And truth be told, dive tables -- called "Recreational Dive Planners" by PADI and just "Dive Tables" by NAUI -- do look complicated and intimidating with their tables and charts and unfamiliar terminology.

Even the supposedly friendly PADI recreational dive planner that every

student must understand before s/he successfully completes the PADI Open Water Scuba Diver course and gets the certification card contains over a thousand numbers on both sides of a small 5 x 7 inch plastic card.

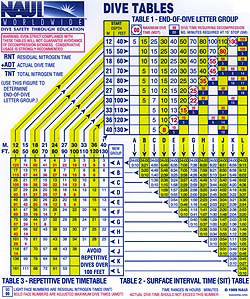

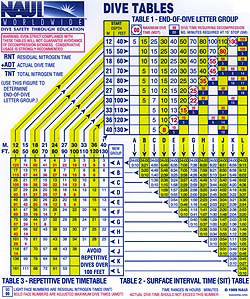

NAUI uses different dive tables, with all tables being on the same side

(see the NAUI table above, and click on it to see a larger copy), but you're still dealing with well over 400 numbers. And there are other formats as well.

What's especially frustrating is that all dive tables do essentially the same thing, just not exactly the same way (and often with surprisingly different results). So the NAUI tables are a bit different from the PADI tables, and they use different definitions and acronyms -- just enough to throw you off. It's like driving a car where the gas is on the left and the brake on the right, and one calls the gas "accelerator" and the other "velocity increasing accentuator". My suggestion is to use and understand one set of tables and stick with them.

So what does a dive planner do?

As explained in the "Physics" and "Physiology" sections, when we dive, our body tissues absorb nitrogen. In those sections you learned that according to William Henry's law, the amount of gas a liquid can absorb

is related to pressure. Since the pressure under water is considerably higher than above water, our body absorbs more nitrogen

when diving, and ever more so the deeper we dive. As we come back up, the pressure decreases, the fluids in our body can carry less absorbed gas, and the nitrogen gets expelled from the tissues again.

For a simple, somewhat dramatic, visual explanation of how absorbed gas leaves a liquid as pressure decreases, picture a bottle of carbonated soda that's been shaken a bit. When you unscrew the cap, pressure is suddenly reduced and the soda foams as carbonation is released. That happens because the pressure inside the bottle dropped when you unscrewed the cap. It's even more dramatic when you pop open a can of beer. Shake either a bit and you really see how gases get expelled from a liquid as pressure suddenly drops.

This same thing is happening in your body as you ascend. Much more slowly and much less dramatically, of course. But it's also much more serious. You do NOT want nitrogen

rapidly bubbling out of your tissues and clogging up your blood circulation or

bubbles getting lodged in other areas. This is why it is essential to slowly and safely release nitrogen as you ascend, and not build up too much in the first place. That is where the dive planners come in. They tell you how long you can dive at certain depths and how long it will take to get rid of all the extra nitrogen in your system.

Recreational dive planners do not actually tell you how much nitrogen is inside your body. They simply tell you how many minutes you can stay, max, at certain depths without having to do decompression stops, something that is not part of recreational diving and that you should never have to do as a recreational diver. The tables have been around for about a hundred years and are all based on data originally developed by the United States Navy. The data is the result of applying the gas laws on the human body, by making certain guesses, developing certain models, and by numerous studies, observations and

tests conducted over many years.

All of that led to the "dive tables" that were first used by the Navy, and then, as recreational scuba diving became popular, modified for recreational use. In 1988, Diving Science & Technology introduced the first dive tables for no-decompression recreational diving. You might guess that the recreational dive tables have a significant safety margin built in. Do not take that to mean you should simply use the numbers as loose guidelines. No way. In fact, if anything, be even more conservative when planning your dives than the table data suggests.

No-decompression diving?

As stated above, recreational dive planners are for "no-decompression" diving. That's unfortunately a rather ambiguous term because, of course, we do decompress as we

ascend to the surface again. What it really means is that the data in the tables shows the length of time you can stay at a certain depth and still be able to

ascend without making mandatory scheduled "decompression stops." Well, you should always make the suggested three minute safety stop at 15 feet. And a minute at half your maximum depth. "No-decompression" diving is also called "no-stop diving" -- because you don't have to make a decompression stop when going up.

How to use the dive tables

Now what do Dive Tables do? They tell you how long you can stay, maximum, at certain depths and then come straight back up, without any decompression stops.

Examples using NAUI Dive Tables

First dive

You're on a dive boat and ready for diving. Using the NAUI Dive Tables shown to the right (Click to see larger

version ), let's say you plan on visiting a reef that's located at a depth of 60 feet.

), let's say you plan on visiting a reef that's located at a depth of 60 feet.

NAUI Table

1, the End-of-Dive Letter Group Table on the upper right of the plastic dive table, shows that the Maximum Dive Time (or MDT) you can stay

at that depth without having to make a decompression stop is 55 minutes (if you have enough air, that is).

It's never a good idea to dive to the limits, so you decide to stay down 35 minutes (which places you in Letter Group G, but more on that later).

You do that dive, enjoy the scenery, and then come back up.

Can you now just use that same dive table, strap on a fresh tank of air, and go right back down for a second look at that reef? No way.

Residual nitrogen after a dive

See, the problem is that while science has determined that it is safe to ascend from 60 feet after 35 minutes -- "safe" meaning that nitrogen gets released at a sufficiently slow rate so as not to pose a danger -- it does NOT mean ALL the nitrogen that was absorbed into your body down there was released during ascent. Think of the soda bottle example again: even if you leave the bottle cap off, the soda doesn't go all flat immediately. Some of the fizz stays in, and only after a few hours or even a day or two does it go all "flat." Same with the nitrogen in the human body. After you're back up, there's still some nitrogen left in your tissues, and it takes time for that to be released.

What that means is that if you dive again, you still have some extra nitrogen in your body, and therefore reach the maximum safe time limit of nitrogen absorption sooner. Which means if you go down to the same depth, you can't stay as long as the first time. And that is what Table 2, the Surface Interval Table, or SIT, of the NAUI Dive Tables is all about. It essentially tells you how much nitrogen leaves your body over the time you spend on the surface, sitting on the deck of the dive boat.

That is where the "Letter Groups" come in. After your first dive you are in a certain Letter Group, as shown in Table 1. That 35 minute dive to 60 feet put you in Letter Group G (you always round up). Table 2 shows what Letter Group you will be in after a certain "surface interval," i.e. the time between the end of your first dive and the start of your second dive. Obviously, the longer you wait, the more of the extra nitrogen your body absorbed during the first dive gets released.

So what the Dive Tables do is determine how much extra nitrogen is still in your body after a dive, and then convert that into "Residual Nitrogen Time," or "RNT." That sounds intimidating, and they really should come up with a simpler term and explanation. As is, "Residual Nitrogen Time" tells you how much time at a certain depth it would take to absorb the amount of nitrogen you already have in your body from the previous dive, and you can find that in Table 3, the Repetitive Dive Timetable. What does that mean? Well, if the table says your residual nitrogen time is 20 minutes for a given depth, then you can stay at that depth 20 minutes less than on your first dive because, after all, you already absorbed that much nitrogen and it still is in your system.

How to plan for the second dive

So let's see how we use the NAUI tables to plan the second dive after our 35 minute stay at 60 feet. We plan on a surface interval of half an hour, and then go see another reef that's 50 feet down.

Using the NAUI table, we find that the first dive put us into Letter Group G. We follow "G" down into Table 2 and then find the new Letter Group for a 30 minute surface interval. That would also be Letter Group "G".

So now we follow the Group G row left into Table 3, the Repetitive Dive Timetable. Then we look at the cell where row G intersects with the 50 feet column in Table 3. There will be two numbers: 56 on top (number in blue) and 24 on the bottom (bold number in red). The top number is your residual nitrogen time (RNT). So on your second dive to 50 feet, you still have as much nitrogen in your system as you'd absorb in 56 minutes down there. The second number, 24, is your adjusted maximum dive time (AMDT), the time you cannot exceed on the dive.

In other words, your actual bottom time can be no more than that. Let's say you decide to stay down for only 20 minutes.

So where do you stand after your second dive? Well, You still had enough residual nitrogen in your system as you'd get from a 56 minute dive, and you now added another 20 minutes of actual bottom time on your second dive. So your total bottom time is now 76 minutes. Now go back to Table 1 and see what Letter Group 76 minutes at 50 feet puts you in. Yikes. At the end of your second dive to 50 feet, you're now in Letter Group "J".

And a third

But let's say you're still not done after your second dive and you plan a third, again to 50 feet. As stated above, although you only stayed for 20 minutes at 50 feet on the second dive, you need to add the 56 minutes of residual nitrogen you still had in your system, i.e. 56 minutes. So the total nitrogen is as if you'd stayed down there for 76 minutes, making 76 minutes your Total Nitrogen Time and you are in End-of-Dive Letter Group J.

If you now plan on waiting an hour and 15 minutes, and then go see that reef at 50 feet again, you find yourself in the new Letter Group H. Now move left to Table 3. Find where row H intersects with the 50 foot depth column and you find that your residual nitrogen time is now 66 minutes and your new adjusted no-decompression limit is now 14 minutes. And so on.

How to back into surface interval time using the dive tables

In real life, reality often interferes with the best laid plans and time is an issue. Let's say you do that first 35 minute 60 foot dive, ending up in End-of-Dive Letter Group G, and then want to see another dive site that's 50 feet down and you'd like to explore for 40 minutes. How long would you have to wait on the surface? Well, start with Table 3, find where the 50 foot column intersects with an Adjusted Maximum Dive Time of at least 40 minutes, and you find it's row E. Move right to Surface Interval Table 2 and see where your current Letter Group, column G, intersects with the Letter Group row you'll be in after that second dive, E.

You find that your surface interval needs to be between 1:16 and 1:59 hours. Just to practice a bit more, assume the second dive goes down to 50 feet again but you'd like to stay for an hour. Now Table 3 shows you're in New Group B. Follow row B to the right to Table 2 where it intersects with column G. Oops. Now you have to wait 4:26 to 7:35 hours between dives. See what a big impact the extra bottom time has on surface interval time?

Backside of the NAUI Dive Table

The NAUI Dive Tables have some explanations and additional rules on the backside. That's important stuff and not to be ignored, ever.

Repetitive Dive -- The term "repetitive dive" refers to any dive made less than 24 hours after a prior dive.

Actual Dive Time (ADT) -- By NAUI defintion, that is the time from the start of descent to the time you are back up at the surface.

Letter Group -- As expained above, for repetitive dive planning purposes it represents the "Letter Group" of the amount of nitrogen that remains in your body after a dive.

Surface Interval Time (SIT) -- That is the time you spend on the surface, between two dives.

Residual Nitrogen Time (RNT) -- Represents, for repetitive dive planning puroses, the amount of nitrogen remaining in your body from a dive, ro dives, ade within the prior 24 hours.

Adjusted Maximum Dive Time (AMDT) -- That is how long you can stay at a certain depth in a repetitive dive. It is the depth you could stay there if it were your first dive minus the residual nitrogen time.

Total Nitrogen TIme (TNT) -- Add up your actual dive time (ADT) and your residual nitrogen time (RNT). That number of minutes is used to find the letter Group after your next dive.

The NAUI Dive Tables also remind that:

- Dives to less than 40 feet depth are treated as 40 foor dives

- Do not ascent faster than 30 feet per minute

- To maximize dive time, start with the deppest dive, and then make each repetitive dive shallower than the prior one.

Examples using PADI Dive Tables

First dive

Using the PADI Recreational Dive Planner tables shown to the right (table removed per demand of PADI legal department), let's say you plan on visiting a reef that's 60 feet down. PADI Table

1, the No Decompression Limits and Group Designation Table, shows that the absolute maximum time you can stay

at that depth without having to make a decompression stop is 55 minutes (if you have enough air, that is).

It's never a good idea to dive to the limits, so you decide to stay down 35 minutes (which places you in Pressure Group N; more on that later).

You do that dive and come back up.

Can you now just use that same table, get a fresh tank of air, and go right back down for a second look? No way.

Residual nitrogen after a dive

See, the problem is that while science has determined that it is safe to ascend from 60 feet after 35 minutes -- "safe" meaning that nitrogen gets released at a sufficiently slow rate so as not to pose a danger -- it does NOT mean all the nitrogen that was absorbed into your body down there was released during ascent. Think of the soda bottle example again: even if you leave the bottle cap off, the soda doesn't go all flat immediately. Some of the fizz stays in, and only after a few hours or even a day or two does it go all "flat." Same with the nitrogen in the human body. After you're back up, there's still some nitrogen left in your tissues, and it takes time for that to be released.

What that means is that if you dive again, you still have some extra nitrogen in your body, and therefore reach the maximum safe time limit of nitrogen absorption sooner. Which means if you go down to the same depth, you can't stay as long as the first time. And that is what Table 2, the Surface Interval Credit Table of the PADI dive planner is all about. It essentially tells you how much nitrogen leaves your body over time.

That is where the "Pressure Groups" come in. After your first dive you are in a certain Pressure Group, as shown in Table 1. That 35 minute dive to 60 feet put you in Pressure Group N. Table 2 shows what Pressure Group you will be in after a certain "surface interval," i.e. the time between the end of your first dive and the start of your second dive. Obviously, the longer you wait, the more of the extra nitrogen your body absorbed during the first dive gets released.

So what the Dive Planner does is determine how much extra nitrogen is still in your body after a dive, and then convert that into "Residual Nitrogen Time," or "RNT." That sounds intimidating, and they really should come up with a simpler term and explanation. As is, "Residual Nitrogen Time" tells you how much time at a certain depth it would take to absorb the amount of nitrogen you already have in your body from the previous dive, and you can find that in Table 3, the Repetitive Dive Timetable. What does that mean? Well, if the table says your residual nitrogen time is 20 minutes for a given depth, then you can stay at that depth 20 minutes less than on your first dive because, after all, you already absorbed that much nitrogen and it still is in your system.

How to plan for the second dive

So let's see how we use the tables to plan the second dive after our 35 minute stay at 60 feet. We plan on a surface interval of half an hour, and then go see another reef

that's 50 feet down.

Using the PADI table, we find that the first dive put us into pressure group N. We follow "N" into table 2 and then find the column for a 30 minute surface interval. That would be column I.

So now we flip the table (told you it was a bit cumbersome) and look at column I. Then we look at the cell where column I intersects with the 50 feet row. There will be two numbers: 31 on top (white background) and 49 on the bottom (blue background). The top number is your residual nitrogen time. So on your second dive to 50 feet, you still have as much nitrogen in your system as you'd absorb in 31 minutes down there. The second number, 49, is your adjusted no-decompression limit, the time you cannot exceed on your next dive. In other words, your actual bottom time can be no more than that. Let's say you decide to stay down for only 30 minutes.

So where do you stand after your second dive? Well, You still had enough residual nitrogen in your system as you'd get from a 31 minute dive, and you now added another 30 minutes of actual bottom time on your second dive. So your total bottom time is now 61 minutes. Flip the chart around and look at Table 1. Yikes. At the end of your second dive to 50 feet, you're now in pressure group T.

And a third

But let's say you're still not done after your second dive and you plan a third, again to 50 feet. As stated above, although you only stayed for 30 minutes at 50 feet on the second dive, you need to add the 31 minutes of residual nitrogen you still had in your system, i.e. 31 minutes. So the total nitrogen is as if you'd stayed down there for 61 minutes, making 61 minutes your total bottom time and you are in Group T.

If you now plan on waiting an hour and 15 minutes, and then go see that reef at 50 feet again, you find yourself in Pressure Group E. Flip the chart once again so you can see Table 3. Find where column E intersects with the 50 foot depth row and you find that your residual nitrogen time is now 21 minutes and your new adjusted no-decompression limit is now 59 minutes. And so on.

How to back into surface interval time using the dive tables

In real life, reality often interferes with the best laid plans and time is an issue. Let's say you do that first 35 minute 60 foot dive, ending up in Pressure Group N, and then want to see another dive site that's 50 feet down and you'd like to explore for 40 minutes. How long would you have to wait on the surface? Well, start with Table 3, find where the 50 foot row intersects with an adjusted no-decompression time of 40 minutes, and you find it's column L. Flip the card and see where your current Pressure Group, row N,intersects with the Pressure Group you'll be in after that second dive, L.

You find that your surface interval needs to be just 9-13 minutes. Just to practice a bit more, assume the second dive goes down to 50 feet again but you'd like to stay for an hour. Now Table 3 shows you're in Pressure Group D. Flip the chart and intersect column D with row N. Oops. Now you have to wait 1:00 to 1:08 hours between dives. See what a big impact the extra bottom time has on surface interval time?

PADI Dive Table "Fine Print"

The PADI recreational dive planner tables have some "fine print" (literally) on the backside. That's important stuff and not to be ignored, ever.

Safety stops -- the optional 3-minute safety stop at 15 feet becomes mandatory if you get within three pressure groups of a no-decompression limit, or for any dive deeper than a hundred feet.

Emergency Decompression -- If for some reason you exceed a no decompression limit by up to five minutes, you must make an 8-minute decompression stop at 15 feet, and then not dive for six hours. If the no decompression limit is exceeded by more than five minutes, you must make a 15-minute stop at 15 feet and then not dive for at least 24 hours.

Air travel after dives -- After a single dive, wait 12 hours. After multiple dives, or several days of diving, wait 18 hours. If decompression stops were necessary, wait more than 18 hours.

Altitude diving -- Special procedures are required if you dive in altitudes in excess of 1,000 feet. (You add two PADI pressure groups per 1000 feet, so if you drove from zero up to mountain pass at 8000 feet, it'd be 16 pressure groups once you reach the summit, and you'd be the equivalent of a PADI "P" diver.)

Multiple dive rules -- Anytime the ending pressure group on the PADI table is W or X, all following surface intervals must be at least an hour. Anytime an ending pressure group is Y or Z, all following surface intervals must be three hours.

Cold water dives -- if diving in cold water, add ten feet to the actual depth.

Dive table assumptions

The standard recreational dive planners from all certifying agencies all make pretty much the same assumptions. They are for standard compressed air, not Nitrox or other mixes. They assume you're diving at sea level or in waters no higher than a thousand feet. They assume you descending at about 60 feet a minute, and come up at 30 feet per minute, and slower for the final 15 feet. If your depth or time is between two columns or rows, alway use the greater one.

For dives less than the shallowest on the table, use that shallowest one. Always do the deepest dive first, and always dive from deep to shallow.

Further, if you dive in very cold water, or do a stressful or strenuous dive, add an additional safety margin. And wait 12 hours til you fly if your total dive time was no more than two hours, 24 hours if more. Any dive within 24 hours is a repetitive dive and must be treated as such.

Have dive computers replaced dive tables?

For most divers, yes, they have replaced the tables. Dive computers, which have been around since the 1980s, do the same thing as dive tables. They estimate nitrogen absorbed and then tell you maximum allowable underwater time (and lots of other data) on the display. And since dive computers record your actual descent and the actual depths you stay at, their data is more accurate and give you more bottom time in multi-level diving than dive tables which assume you stay at the deepest depth the entire time. Dive computers also eliminate human error. However, understanding dive tables helps you understand the reason behind the numbers the computer displays. In addition, even the best dive computer can fail, so knowing how to use the dive tables, and taking them along is a good idea.

One potentially serious problem with dive computers is that they're all different. They may show the same information, but operating them can be an exercise in frustration as there are no standards. User manuals are generally confusing and/or poorly written, and there are no courses that teach how to use a dive computer, with explanation of how to operate the major brands and models. As a result, most recreational divers simply dive without truly understanding their dive computer.

Some dive computers are "air integrated," which means they know the air pressure in the tank and can calculate remaining air time based on depth, current consumption rate and remaining pressure. Some don't even need a pressure hose and get the data via a wireless transmitter instead. That means one fewer airhose that can get tangled up somewhere.